Berlin

After my parents divorced in 1973, my mother took me and my two brothers to live in Israel. We were at the tail-end of a large movement of Americans who immigrated to Israel after the 1967 Six-Day War, most of whom moved for religious and ideological reasons.

My mother, like many American women of the time, had grown dissatisfied with her role as a homemaker and wife, and had started to push the envelope of what was expected of her. For a long time I thought of my mother as confused post-divorce, but speaking to many who knew her back then, she was in no way confused. She knew she was going to need help raising her three children; she had also heard about the socialist environment of Israel’s kibbutzim, and felt a sincere desire to “get back to her roots” of Judaism. She sought out and found the Israel Aliya Center and won sponsorship from the World Zionist Organization, which organized and helped fund our move to Israel. We spent nearly four years living on kibbutz Mishmar Haemek, which is one of Israel’s oldest and largest kibbutzim, and still exists today. Nicknamed the “Guard of the Valley”, it’s situated in northwest Israel, a 30-minute drive south of Haifa. I lived there from ages 7-11, formative years which have shaped much of who I am today.

Every year, each children’s house would visit the Holocaust memorial, located on the kibbutz property during Yom Kippur, one of the Jewish high, holy days of atonement. We were asked to walk silently, and led into a courtyard with one building and three short walls. I remember the walls were made of large, rectangular stones, gray in color and a bit rough and oddly shaped. The ground was covered in cobblestone, though the entrance was covered with leaves from overgrown trees, just as at the start of Autumn. We learned about about how the Jews had suffered, first as slaves in Egypt and then in the Holocaust by the Germans.

We were asked to think about and deeply feel the pain, misery, and sacrifice of our people; we were asked to set aside the fun times we were having in the children’s houses and consider how many people had lost their lives so that we could be somewhere safe. We were told we needn’t worry, but that we should be grateful to be living in Israel, our promised land. We were taken on the same field trip every year at Yom Kippur.

By 1980 I was 12 years old, and back in America, living in Ashland, Oregon. One evening as I was lying in bed, somewhere between waking and dreaming, I felt my body seize up and become as rigid as a plank of wood. I started to see myself being led into a crematorium and facing a row of blazing hot steel ovens, flames visible through a small window at the top of each door.

One of the doors opened and a steel bed rolled out, the hottest fire I could imagine at the oven’s belly. I climbed in, laid down, and was rolled in. The imagined screaming woke me up. I felt what seemed like a conscious sensation of being trapped and burned alive, and I could feel the finality of death through my body. It was a completely disembodying experience, and it carved a deep wound somewhere inside.

I started to wonder where such visceral ideas and feelings had come from, and why I had been so scared of Germans and Germany as a child. I vaguely remembered having heard fearful stories of German people from my mother and grandmother, though my mother also made jokes about Germans, putting on a comic fake accent. She died in 2003 and I inherited her books, among other things, including a kind of illustrated encyclopedia titled The Wonderful Story of the Jews, written by Jacob Gewirtz. It was published in 1971, not long before our move to Israel. The text refers to the German’s “unspeakable crimes” against the Jews, as well as the “unending ravages of war, persecution, and tyranny” they have faced; some of the illustrations are quite scary, showing buildings on fire and Jewish people menaced by gun-wielding Nazis. The book presents Israel as a place of refuge, the Kibbutzim as almost unique.

When my parents divorced my mother was just 25, and had three boys attached at her hip. Those who knew her then say she was idealistic, practical, and brave, not given to introspection. I can easily imagine she looked to this book for solace, as a guide to living through difficult times. But I also wonder how it influenced her, and in turn how it influenced me.

In 2008, a friend suggested I photograph Berlin. He thought the city would be a good match for my sensibilities, but I met his suggestion with trepidation and fear. I harbored many preconceived ideas about Germans and Germany. I imagined Berlin as a vast, cold, unfriendly, gritty place, but at the same time, it seemed exciting and sexy somehow.

I decided to see Berlin for myself, keen to challenge my existing ideas and also uncover reminders of the Jewish people who had lived there, until they fled or were hunted down and killed by the Nazis. I would spend the next five years reconciling my feelings and associations with Germany and the German people and writing a new narrative.

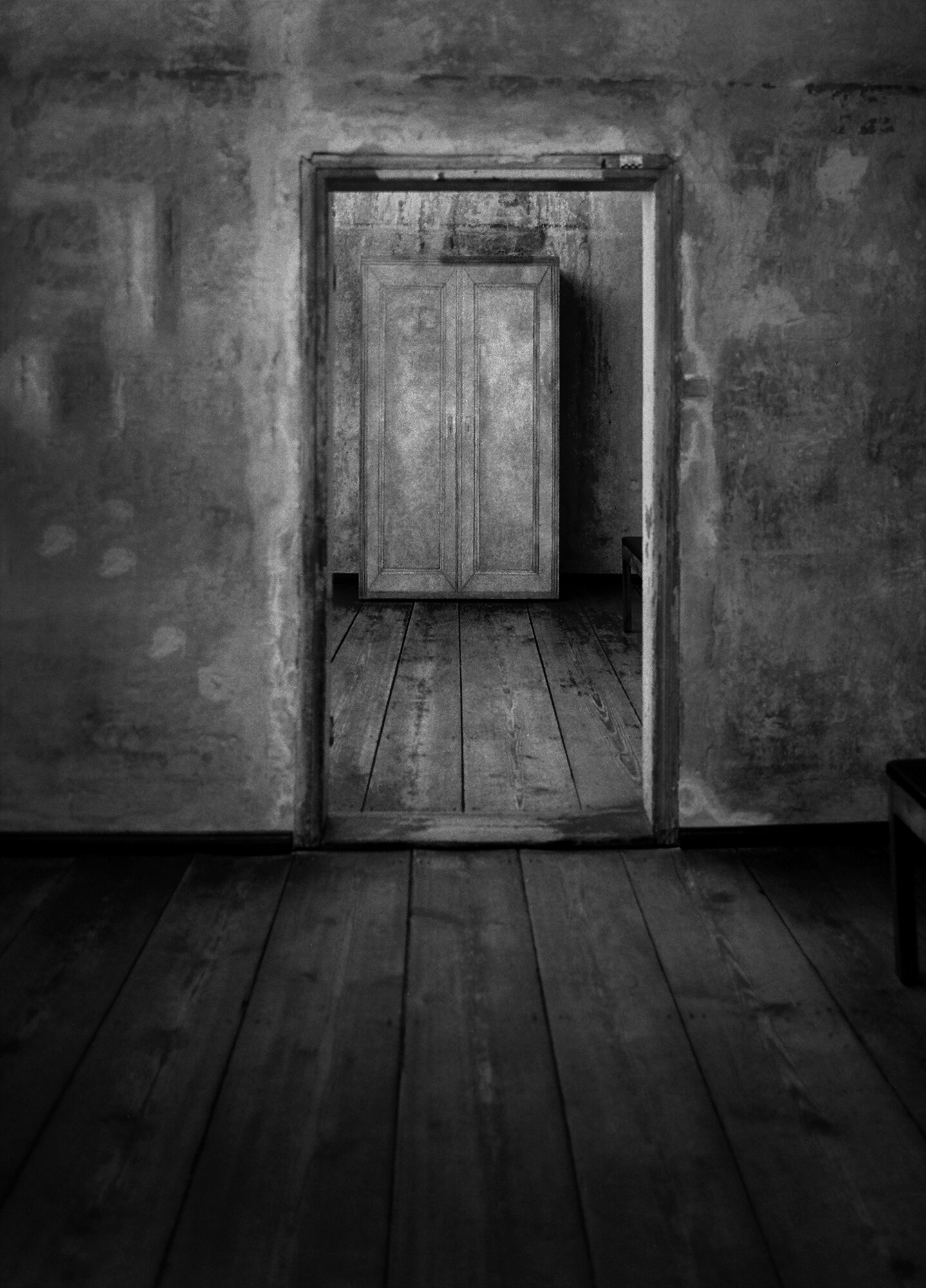

I wandered the streets making work, attempting to walk through my own looking glass towards the now. This work is an attempt to remember, confront, and unwind my attitudes about Germans, Germany, Berlin, and my Jewish inheritance; these images are part discovery, part remembrance, and part fantasy. They’re my attempt to stand where Jewish people were rounded up and deported, to remember but also reassess. They’re an effort to confront my internal attitudes and prejudices, to look into people’s eyes and find a continuation of kindness, to be open to the happiness of contemporary life in Berlin.

I followed the thread of the Holocaust because somehow it’s still in me, though I was born in 1967 in Tuczon, Arizona. I feel it inside, buried under the layers of my family’s fears and my childhood experiences. I imagine it’s in my kids too. Knowing that I’m a link in a chain of survivors comes with weight I can’t take lightly or cast aside.

In Berlin I worked alone, imagining all who had walked where I was walking, those who had taken the same route as me, going to the same places. I wondered what they looked like and what was on their minds, what they were wearing, who they were with, and how long they lived. Berlin is full of ghosts. Whenever I had the freedom to wander, I took it as a gift of prolonged, uninterrupted time for reflection. For the most part no one bothered me. I felt invisible, as if I were floating above the city, swooping down occasionally to timidly snap a photo or two.

Once in a while, I found the courage to ask someone if I could photograph them. My approach was direct. I made one or two shots of each person, noted their name, thanked them, and kept going. My only direction was that they should look into the camera, and I always apologized for not knowing German. I found that most young people spoke to me in English anyway, and encountered very few who refused my camera. In between photographing places of pain, I would visit my friends and make intimate photographs of them, usually in repose. It was a strange mix of death and life, pain and pleasure; life, death, and giving life again. There was a sense of youth, freedom and joy I felt in Berlin and found a way to do that with casual, affectionate pictures of my new friends.

The photographs are organized geographically from West to East, a metaphorical walk in the direction of the rising sun but also into my own past. This book is not a document, it is a dream within a dream within another dream. Berlin is immense, there was no way I could cast a wide enough net to what it’s like; instead I have painted a picture of then and now, pain and pleasure, some people who died long ago, those who are living and young, all from my own perspective.

© Jason Langer, 2021